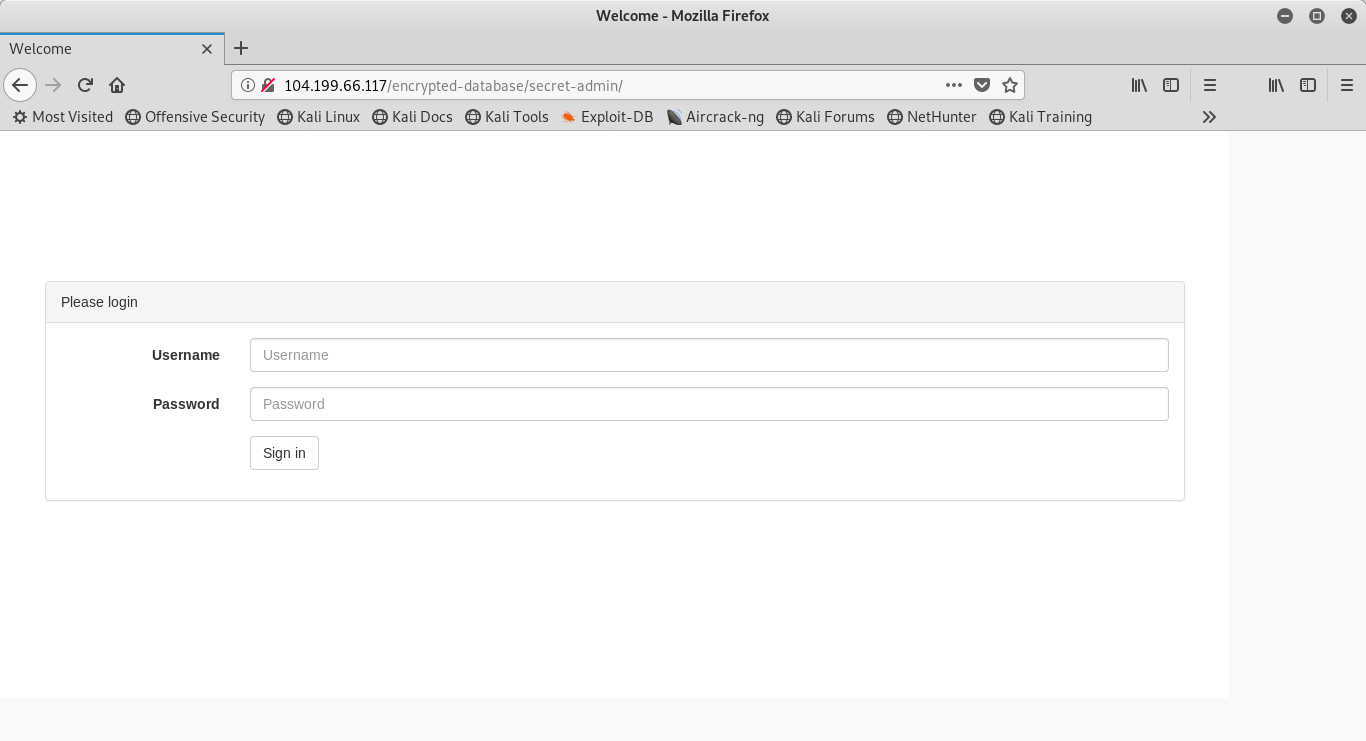

Let’s begin by opening our web page to take a look around. This is what we find:

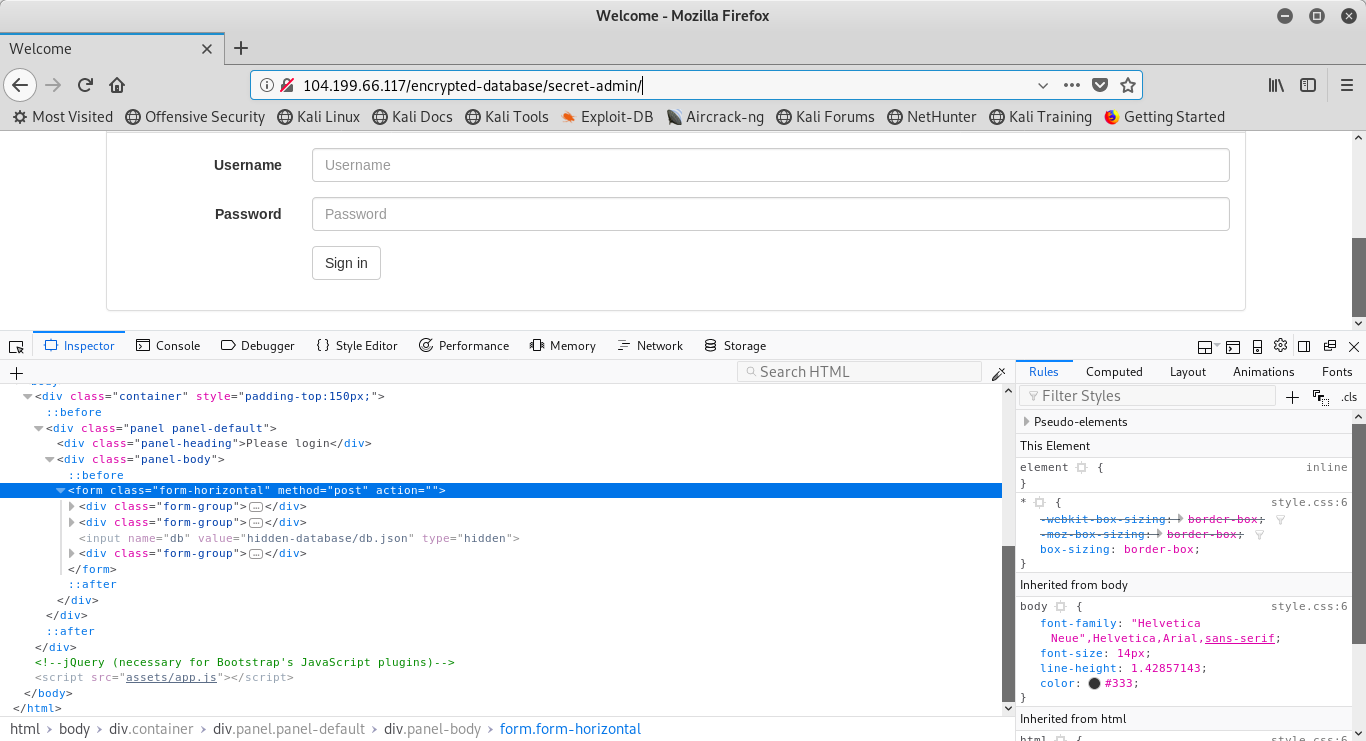

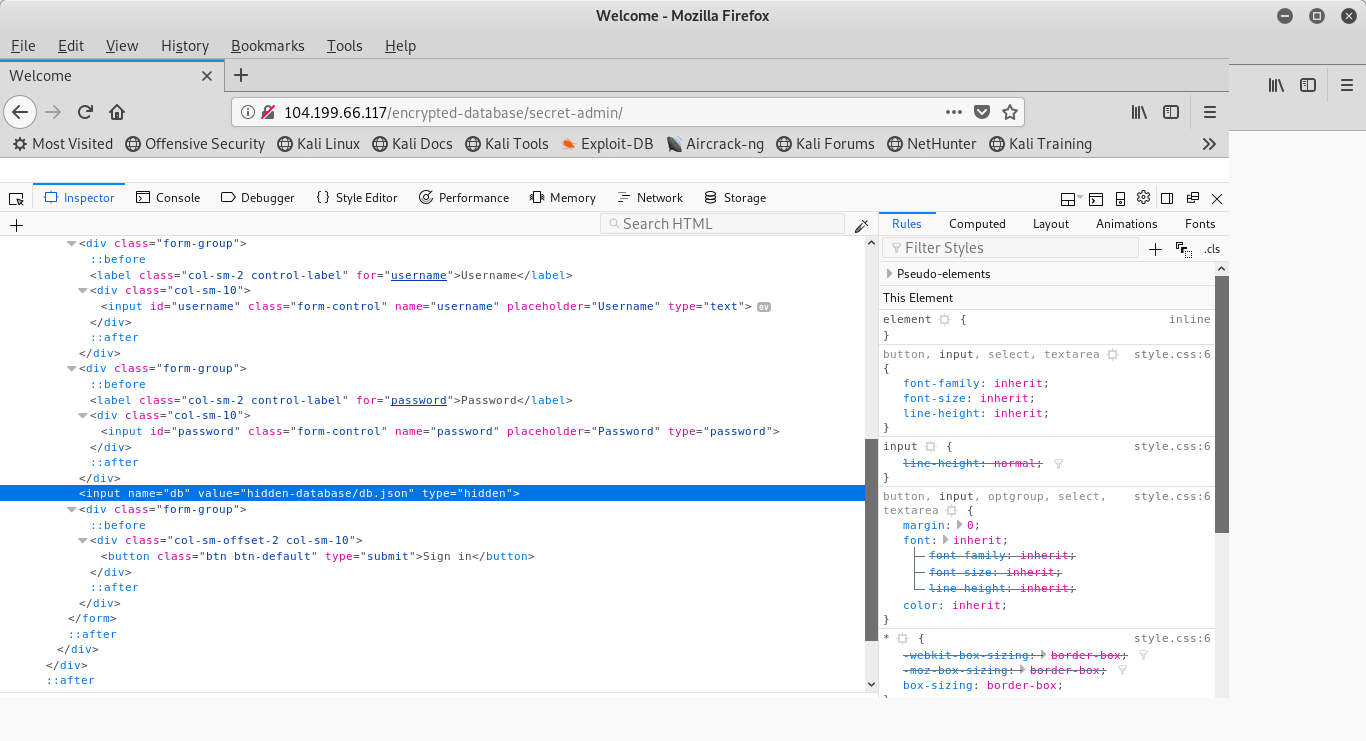

The first thing I choose to do is poke around the website and take a look at the links in the top left corner. The url doesn’t change, so it doesn’t look like a plausible web-parameter tampering. Upon inspection, there are no login or search fields, so it doesn’t look appear eligible for SQL injection. So I inspect the element and this is what I find:

Notice this following line of code in the HTML:

http://secret-admin/assets/app.jsNaturally, the first thing I’ll try to do is traverse to that file and see what happens. When adding this to the end of the url, we find this:

jQuery. Not particularly helpful.

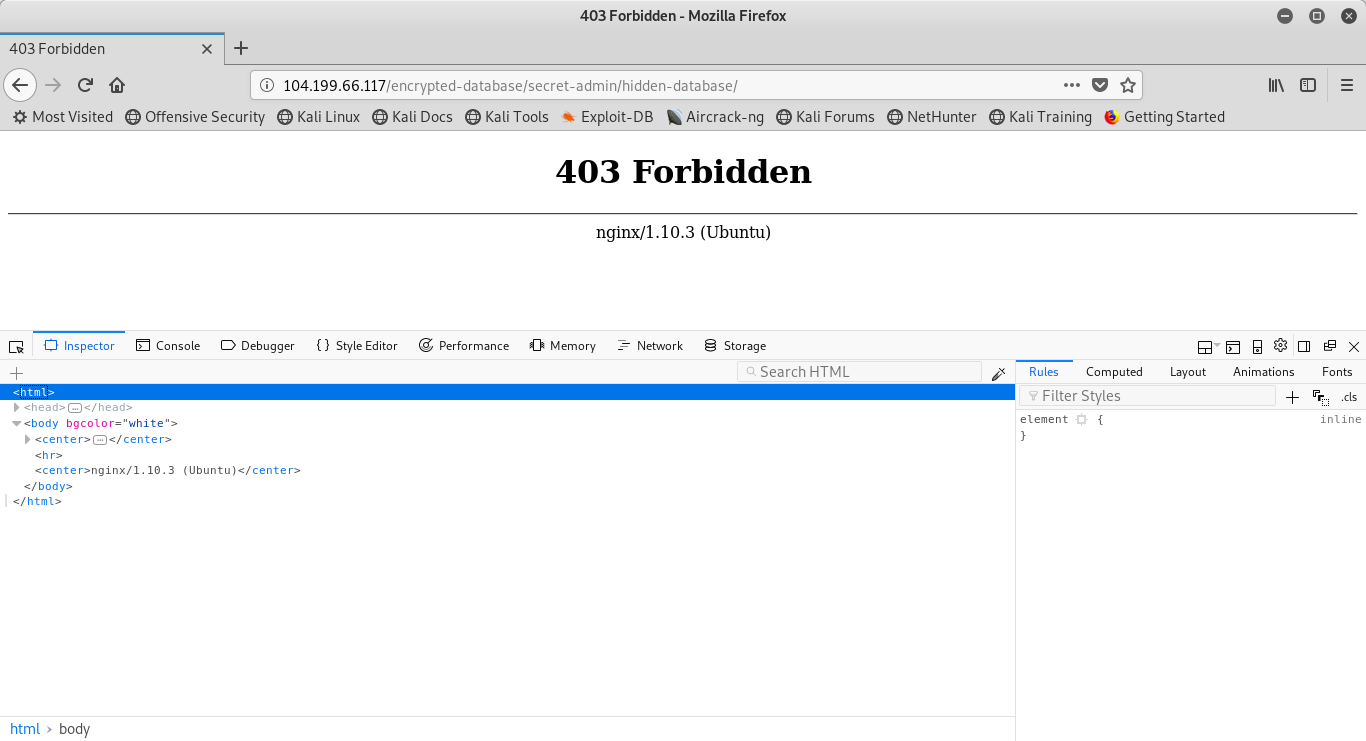

Let’s try this again, but going back one directory:

This wasn’t much help either. Let’s go one more:

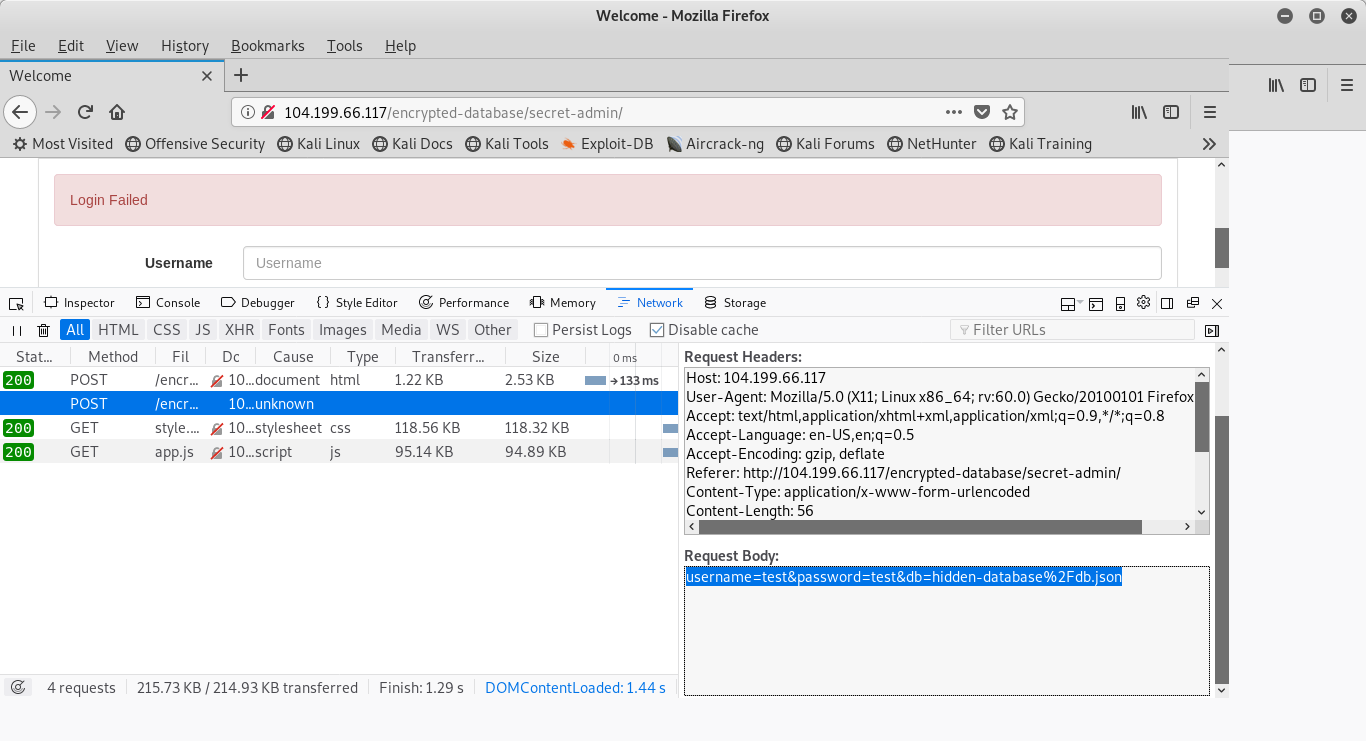

Finally, something that looks promising. Since I have no idea what the username or password would be, let’s consider trying SQL injection! To do this, we first need to follow a post request and see what the request body looks like in the header. We will use a username and password ‘test’ to accomplish this task. This is what we find:

We have a request body of username=test&password=test&hidden-database%2Fdb.json. Now let’s take our parameters and plug them into SQLMAP to see if we find anything. We’ll use the following command

sqlmap -u http://104.199.66.117/encrypted-database/secret-admin/ --method=POST --data='username=test&password=test&hidden-database%2Fdb.json'All fields returned back non-injectable. A quick test of entering a single ‘ shows doesn’t throw an error, so I decide to investigate more prior to retrying SQLMAP with a higher level (I’ll only do 1 or 5. If I do anything in between and it turns up with nothing, I’ll wonder if 5 would have caught something.) Let’s take a closer look at the HTML:

Here, we have a hidden input field of value=hidden-database/db.json, which is the same as the database parameter in our SQLMAP attempt. Let’s try to navigate there and see what we find.

Hey! It’s our flag! All that should be left to do is type that into the submission field on CyberTalents, right? Wrong. After many attempts (and rereading the prompt) the database values are encrypted which would lead me to believe that the decryption of this is the flag.

While I could use John the Ripper for this flag, there’s a much faster option to try for a first attempt. This happens to be the BEST password cracker in existence. It can process billions, if not trillions of hashes in a single second to compare to its gargantuan database.

It’s Google.

A quick search yields the following results:

Without even clicking on a link, I can see that this is an MD5 hash of the password ‘badboy’. Just for fun, let’s try to crack it using John as well. Since we know the format is MD5, and it’s a common password, let’s take a look and see what John does with the default password list:

There it is. Confirmed that our hash is a indeed an MD5 of ‘badboy’. It should be noted that I first had to do a nano hash.txt and paste the password hash into it to make this work.

I always try Google first. With this particular password, John detected it as an LM hash and not an MD5, so it would have taken a lot more work to try and get John to make it happen on it’s own.

All of this goes to show that weak passwords are never safe. They can’t be saved with encryption or salts, because a password like this doesn’t warrant Rainbow Tables anyways. John literally cracked this password in just a few seconds on an old, slow computer. And remember: password length is your best defense against unauthorized hacking.

thanks so much for your decent and honest explanation 😉 love you bro.

ston3 from Oman.

LikeLiked by 1 person